Things I hope you learn from this post series:

- Part 1 (you are here): Why do we use fiber optic cables?

- Part 2: What is a fiber?

- Part 3: The very basics of optical communication, but also some super advanced stuff

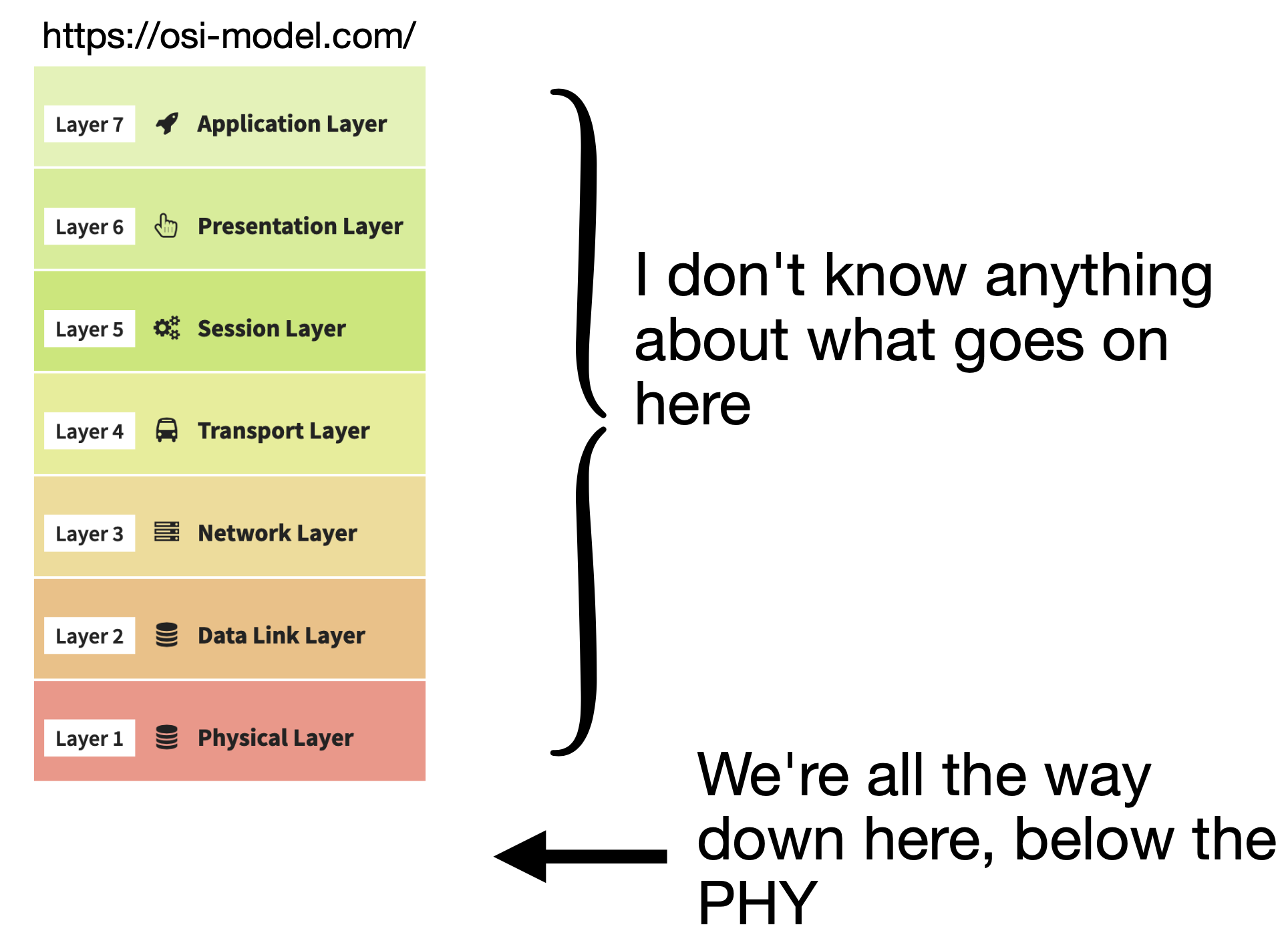

This will be about how the physical ones and zeroes get from point A to point B in a fiber optic cable. Expressed in terms of the OSI model, this is usually lumped in with the PHY, or even below the PHY depending on who you are talking to. I don't have a clue about how the networking systems themselves work. The PHY is at a higher level than what I personally understand.

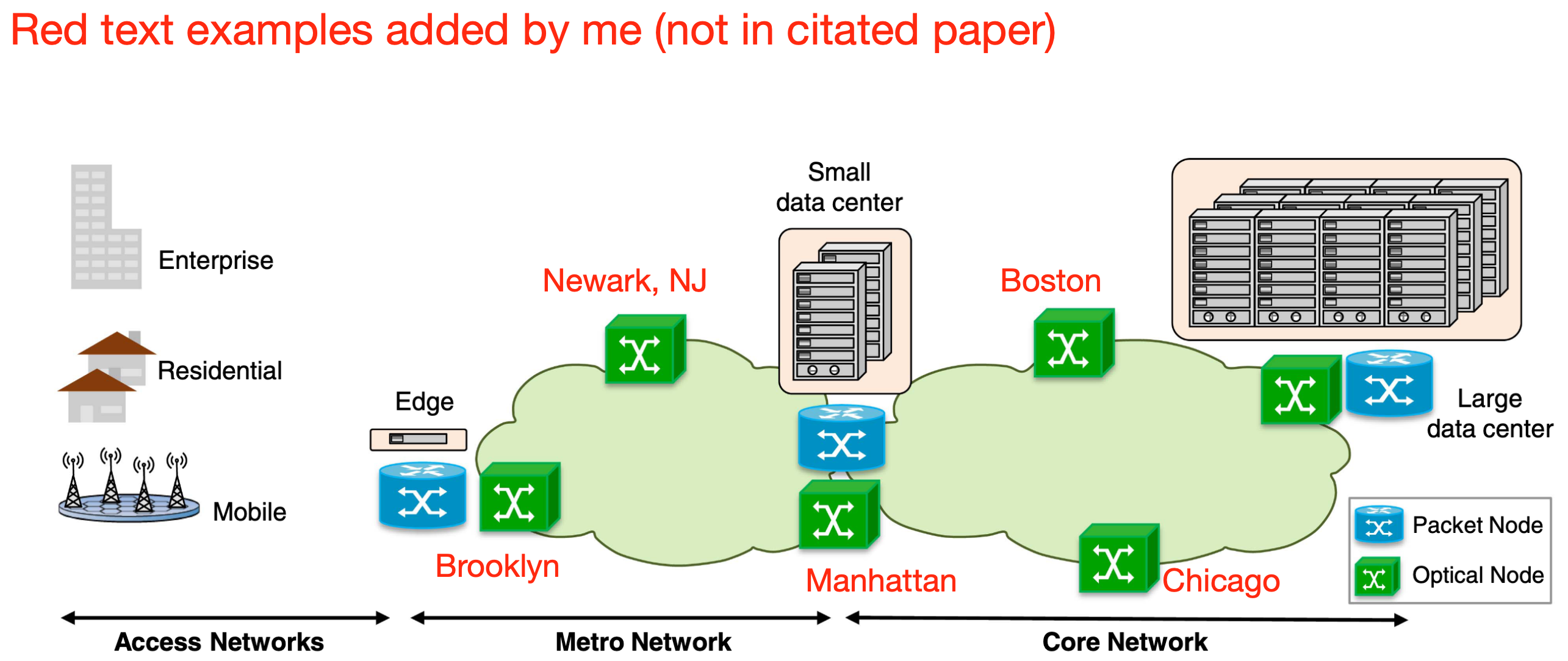

To give some context for what kind of fiber optic communication we will be talking about, here is a cartoon of a telecommunication network:

What you might be more familiar with is the fiber optic cable that would go to your home (or maybe just your dream home). The stuff connected to your home, a business, or a cell tower is usually lumped into the category of connections called access networks. From your home, a cable might go to a switch that connects to multiple homes, out of which there could be cables to another aggregation location, eventually all leading to some central office. This central office is itself connected to several other pieces of aggregation and networking infrastructure. This part of the network is the "edge" and eventually leads to an edge connection in a metro network. While some of the topics covered in this post series will be useful for understanding the connections from your home to the network edge, the actual transmission systems described down below are mostly only used in the metro network and higher.

Fiber optic cables might connect Brooklyn to Manhattan to Newark, NJ. Maybe there is a small data center in Manhattan that is connected to this metro network (and in reality, there are so-called data center interconnects connecting data centers within a metro network to one another directly). The fiber optic cables within the metro and core networks operate at anywhere from 100 gigabits per second (Gbps) to more than 10 terabits per second (Tbps). We'll start with why we might even use a fiber optic cable, and build up to how to transmit information at these tremendous aggregate data rates

Why do we use fiber optic cables?

We use fiber optic cables instead of copper cables because they have superior bandwidth. What having "good bandwidth" means is a little bit nuanced, but it is sometimes synonymous with "faster." An oft-repeated but incorrect statement is that the fiber optic cable is faster because the signals travel at the speed of light instead of the speed at which electrical signals propagate down a fiber optic cable. In actuality, the speed of propagation of electrical signals in high-bandwidth copper cables is almost the exact same as the speed of light within a fiber optic cable.

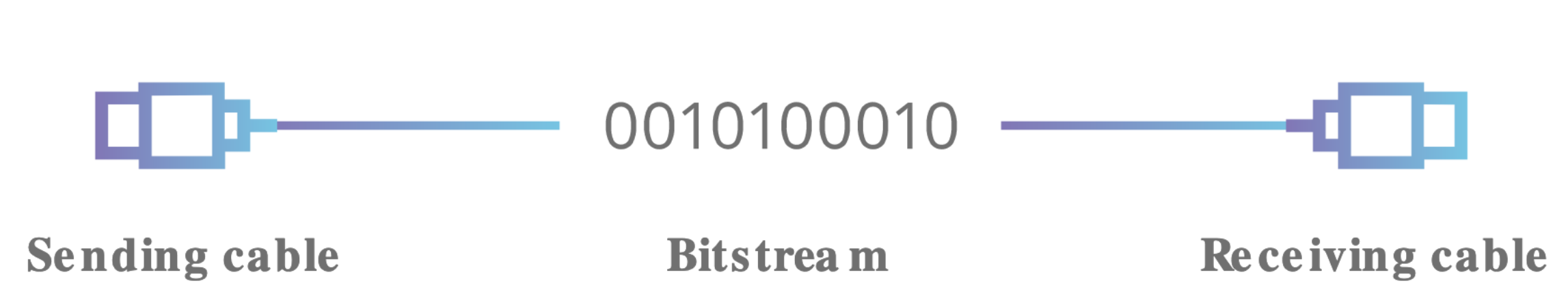

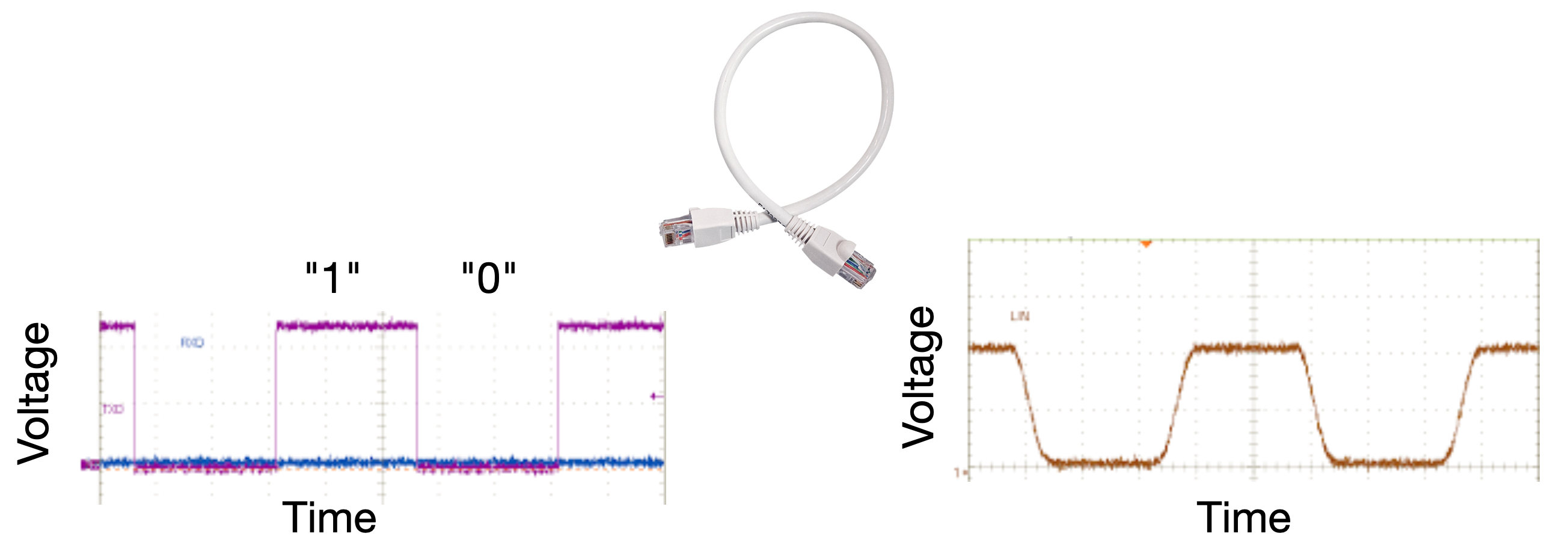

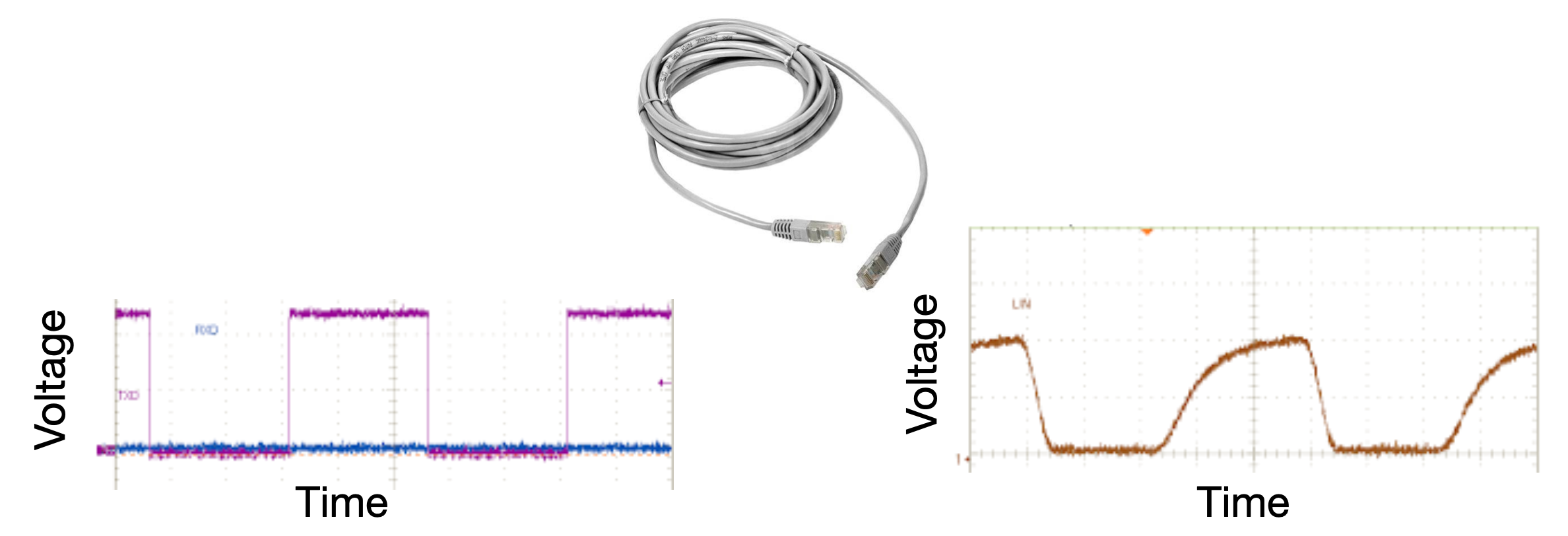

Diving into bandwidth a bit more, imagine we have a short copper cable connecting two points. On one end of the cable we switch an electrical voltage from a high voltage (a binary "1") to a low voltage (a binary "0"). At the other end of the cable, the transition from "1" to "0" and vice versa will not be as quick as at the starting end of the cable:

As the electrical cable gets longer, the rise and fall time of the ones and zeros increases:

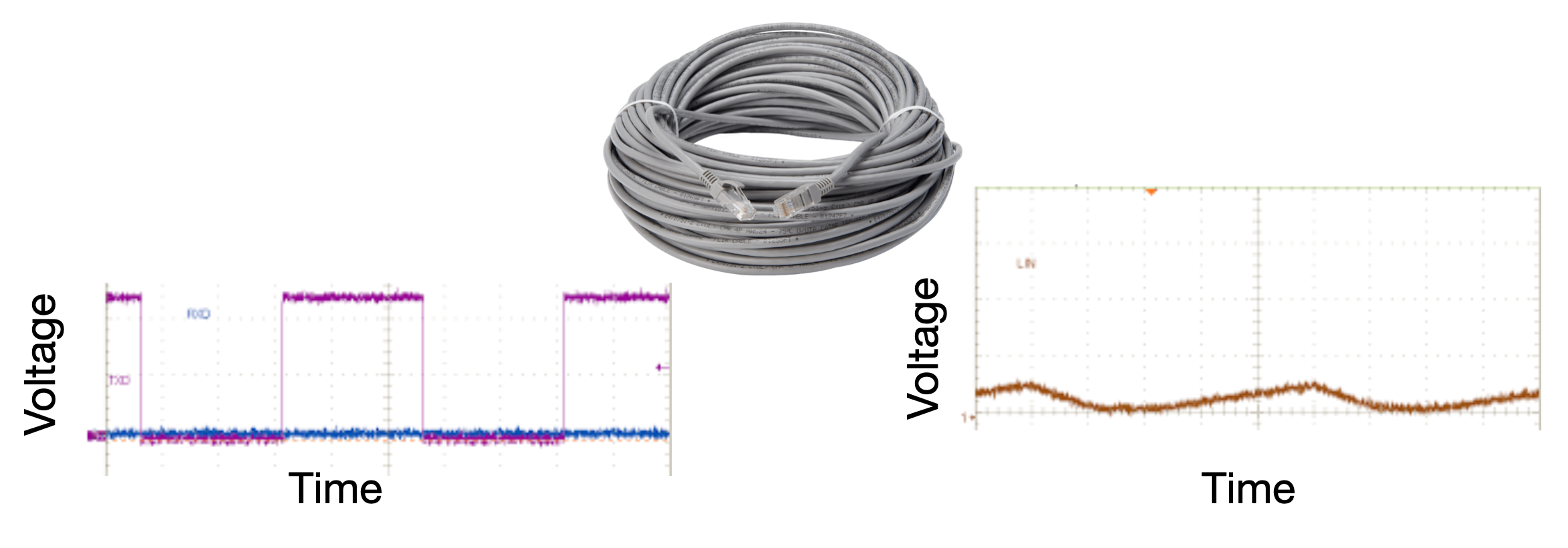

And eventually, at a certain length the rise and fall times pretty much prevent us from recovering the original signal:

With that last really long electrical cable, if we slow down the rate at which we switch (for the sake of argument, say we go from switching 1000 times per second to 500 times per second), we can start to see the original signal again:

The key thing to take away from the above is that a copper cable has some fundamental limit related to the data-rate times the cable length: The longer the cable, the slower you are forced to transmit data (switch from one to zero, and vice versa).

A natural question you may have is "why do the rise and fall times depend on the length of the cable?" An answer that only touches on the subject is that an oscillating voltage signal is attenuated as it propagates along the length of the cable. There is some neat physics involved that I won't go into further here.

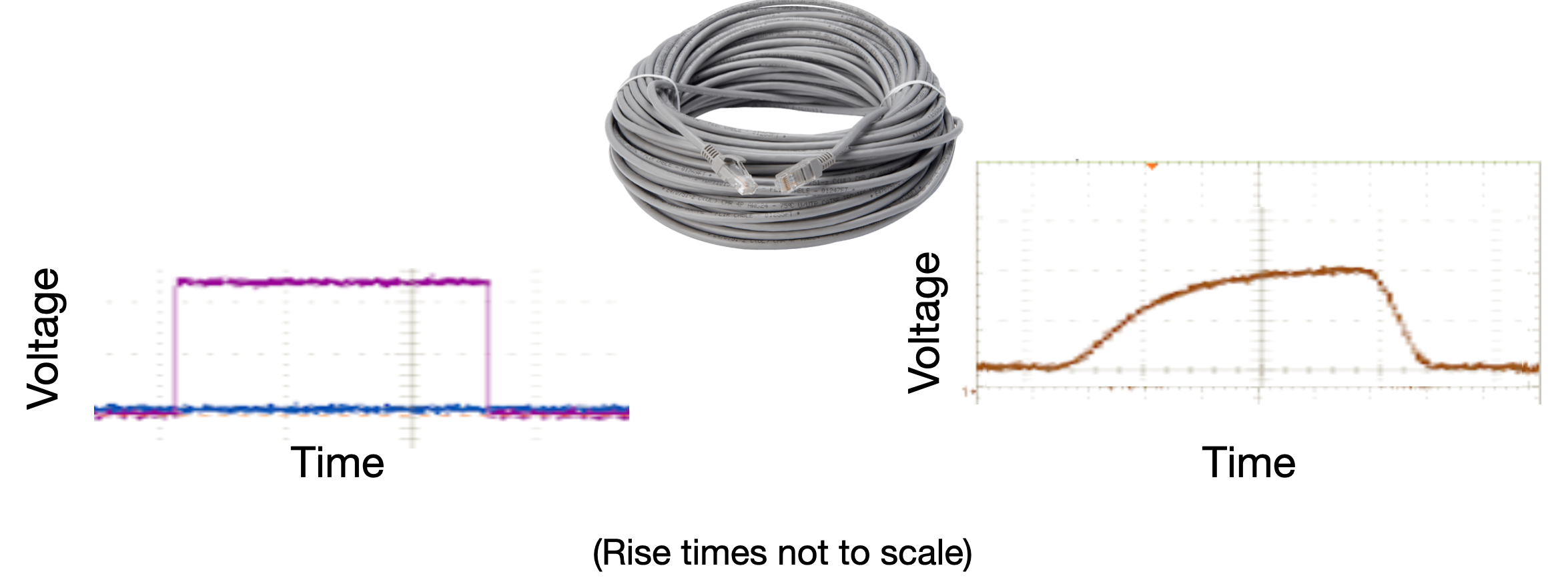

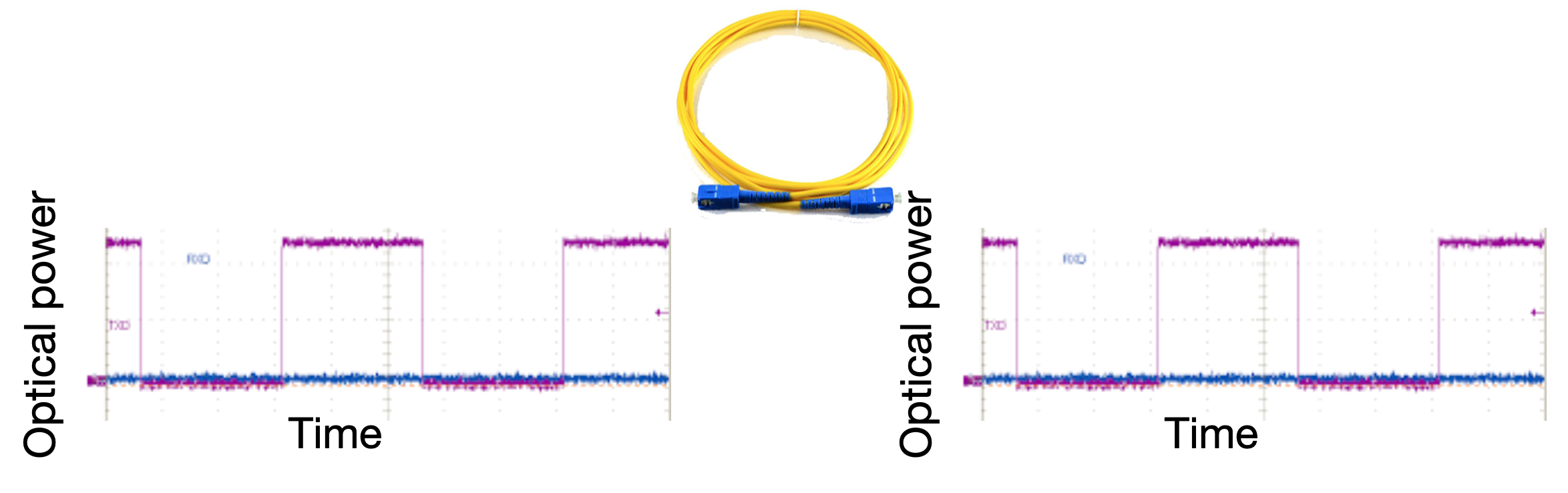

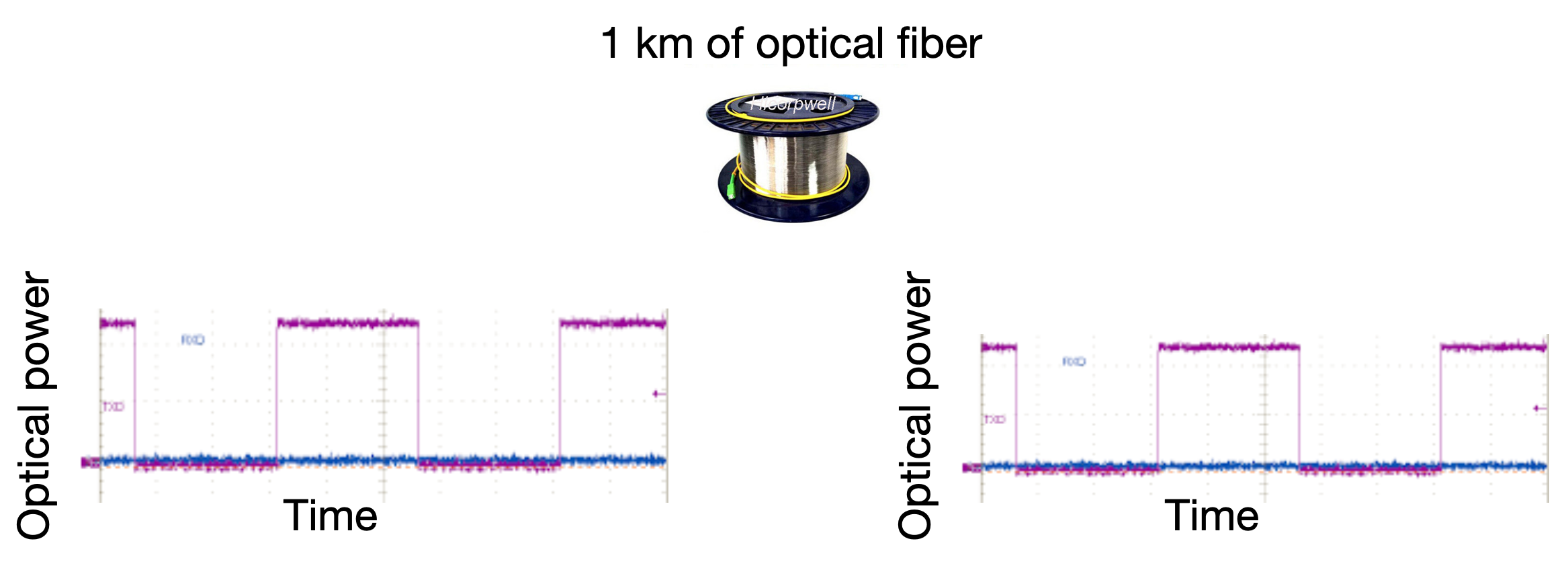

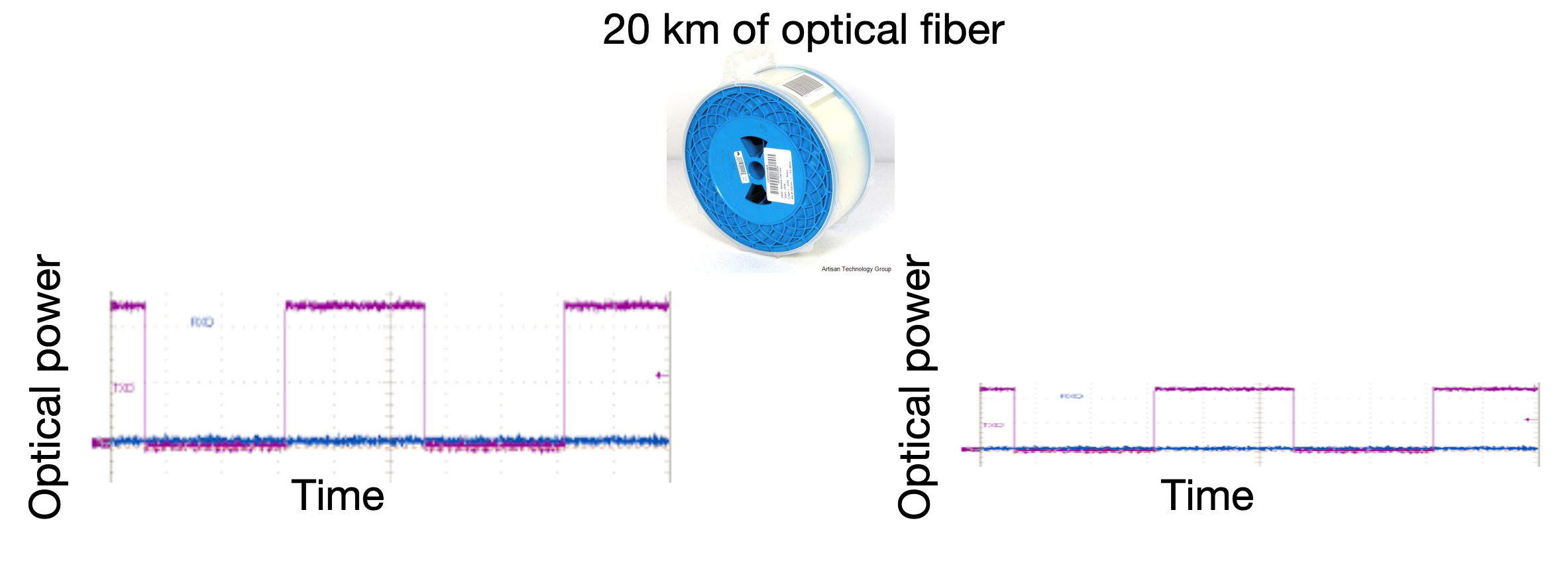

A fiber optic cable does not, in general, have this same limit. (This is mostly true, but I won't go into the ways it isn't in this post). If we start with a relatively short cable, and instead of switching an electrical voltage, we turn a light source on and off to represent our ones and zeros:

... and increase the length:

... and increase the length by a lot:

You can see that the rise and fall time at the end of the fiber are the same as what they were at the transmitting end. (Again, this is only mostly true, but the reasons it isn't aren't important now). The optical fiber isn't perfectly transparent, so the light is diminished in intensity as the cable gets longer, but the rise and fall times aren't affected.

The other oft-repeated and correct reason we use fiber optic cables is because they can support multiple colors, with each color carrying its own data signal. Pink Floyd helps us with the visualization:

The science of how many colors a fiber optic cable can carry is, you guessed it, also nuanced. In practice, the upper limit for today's transmission systems is close to 100 colors per fiber, with the actual number varying depending on the data rate, transmission format, and a variety of network parameters.

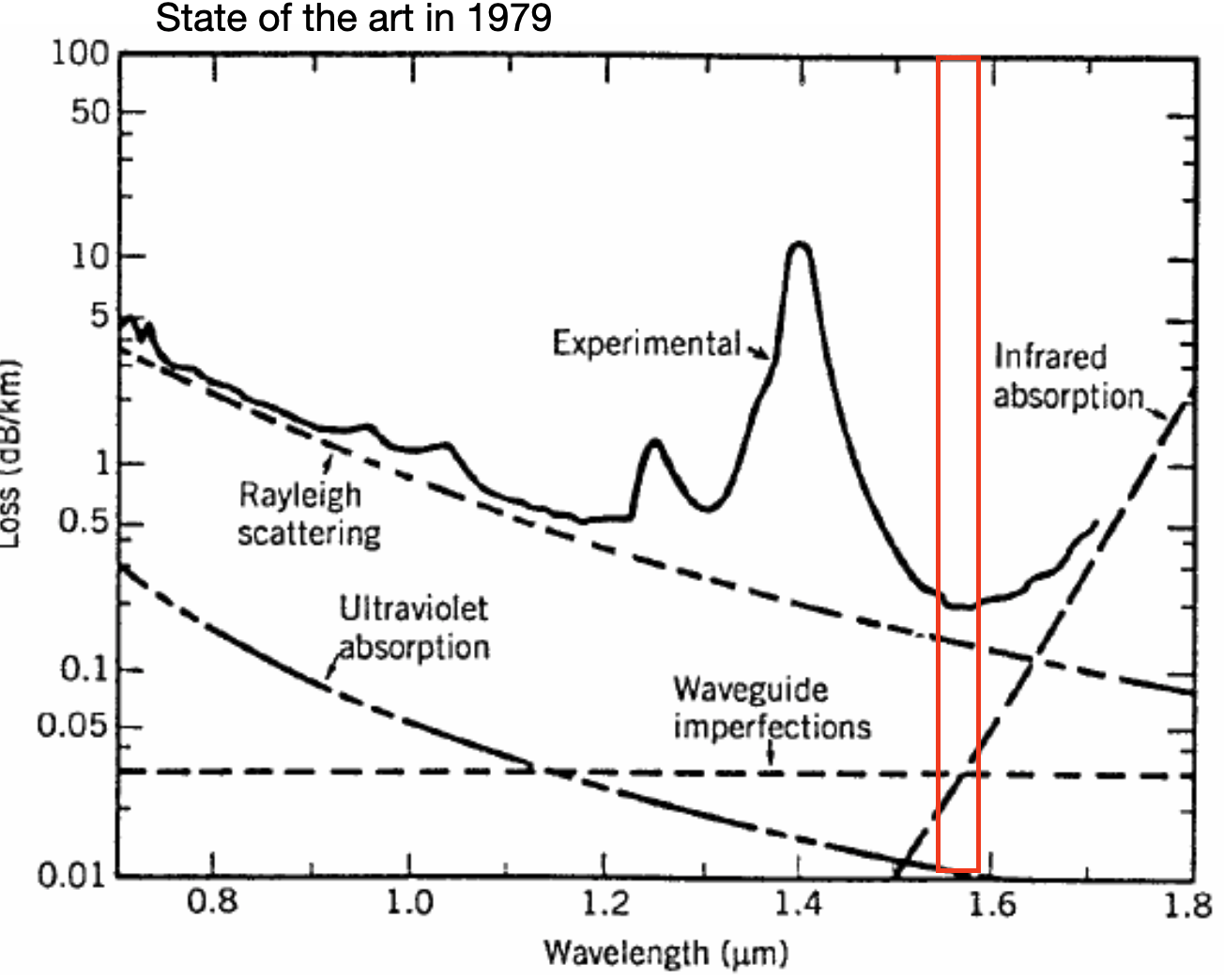

Most telecommunications systems operate in the telecom C-band, at wavelengths of roughly 1525nm to 1565nm. As a reminder, the visible spectrum is roughly 380nm to 750nm. There are two primary reasons for using the optical C-band for long-distance communication. The first is that a typical optical fiber is the most transparent in this wavelength range. Being more transparent means you can transmit more data farther before your light is too diminished in intensity to recover. This plot of loss (smaller numbers means the fiber is more transparent) versus wavelength was the state of the art in 1979 (and since then, some of those peaks have been pushed down close to the fundamental limit):

The other, and presently in 2020, more important reason we primarily use this wavelength range is due to the physics and availability of optical amplifiers, most commonly an erbium-doped fiber amplifier. An optical amplifier is a device in which you can input your optical signal and get a brighter version of it out the other side (plus a little bit of noise because nothing is perfect). The amplifiers let us transmit signals over tremendous distances without using repeaters to receive the optical signal, convert it into an electrical signal, and regenerate a new optical signal. Part 3 of this post series will go into the historical scaling trends in a bit more detail.

Summary: Why do we use optical fibers instead of copper cables?

Optical fibers are "faster" than electrical cables in terms of transmission capability: more bits per second per distance.

In Part 2: What is a fiber? I will tell you what a fiber is and so much more!