Part 2.0: Building blocks

Oftentimes, when someone comes up with a fabrication process for building silicon photonics wafers, they also go ahead and build a set of "building blocks." In fancy-speak, we call these building blocks part of a "design kit," or "process design kit," or "PDK" to refer to those building blocks along with guidelines for how to design circuits within a certain fabrication process.

The set of building blocks someone could come up with are, quite literally, infinite in number. In practice, there are a few key functions that an engineer will implement. For the sake of this blog post, I will just talk about a couple of them. What you will quickly discover, though, is that a tremendous number of things can be created by putting these blocks together.

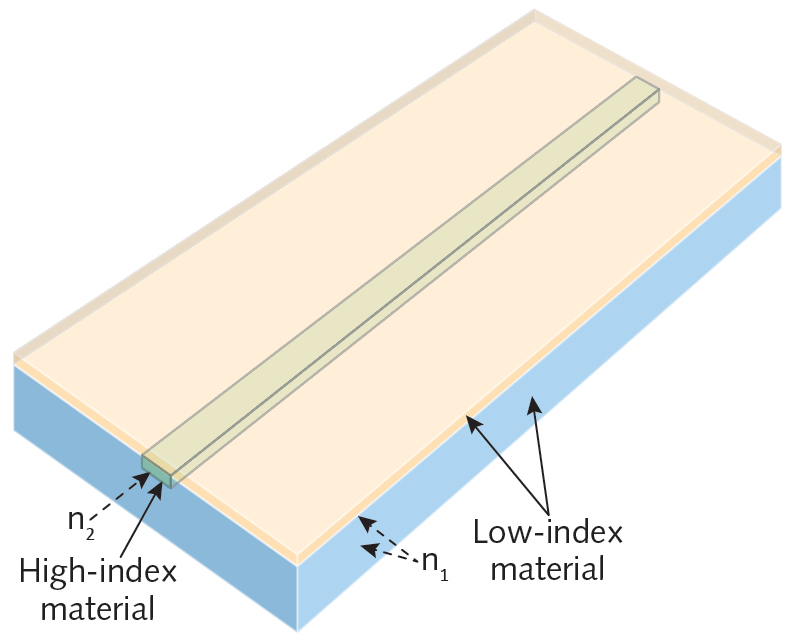

Waveguides

Think of a waveguide just like an optical fiber (What is a fiber?). A waveguide sends light around a chip. Oftentimes, waveguides are just rectangular tubes of material. Like an optical fiber, usually the critical element of a waveguide is to have some material with a high refractive index surrounded by another material with a lower refractive index.

Light goes in one side of a waveguide and most of it comes out the other side. For the sake of simplicity, throughout this blog post I'm going to draw waveguides as 2-D images. For example, here's a single segment of a straight waveguide:

Importantly, waveguides can also make turns just like a bendable optical fiber:

Splitters/combiners

Bending waveguides is useful. If you have two waveguides and bend them near each other, light will transfer from one waveguide to the neighboring one. The amount of light transferred will depend on how close the two waveguides are and for how much length they run next to each other. We call this device a "directional coupler." Directional couplers can be used to "split" light from one waveguide into two waveguides, as well as "combine" light from two waveguides into one waveguide. Try dragging the length of this directional coupler so that all of the light goes into Output 2:

Phase shifters

Phase shifters are perhaps the most important capability for silicon photonics. A phase shifter is a device whose refractive index can be manipulated by an applied electrical signal, a change in temperature, or some other mechanism. This part might be hard to wrap your head around. Light is a wave with an amplitude (how bright it is) and wavelength (what color it is). In a vacuum, if light propagates 1 wavelength of distance, then it will have gone through a full 360° of phase change (and so the net change in phase is 0°). If it propagates through a thousand wavelengths, it still effectively has not changed in phase. Instead, if it passes through 1/4 of a wavelength, then it will have changed 90° in phase from start to finish (360° / 4 = 90°).

Changing refractive index of a material that light is propagating in can be called a changing the phase of the output light that passed through it. This is because changing the refractive index changes the effective distance that light is travelling. So if you change from a thousand wavelengths of distance to a thousand and a quarter wavelengths, you will have created a 90° phase change. Drag the voltage applied to the phase shifter below. Notice how as you change the refractive index, the phase of the output changes (The far right side of the image will end at the peaks of the sine wave or the troughs or somewhere in the middle depending on the refractive index of the phase shifter material).

Photodetectors

Opposite from phase shifters (taking an electrical signal and changing a property of an optical signal) are photodetectors (taking an optical signal and generating an electrical signal). The gist of a photodetector is that a particle of light, a photon, gets absorbed by the photodetector and generates a particle of electricty, an electron. In an ideal case, every photon generates one electron.

Brighter light is essentially more photons per second. An electrical current is essentially the number of electrons flowing per second. If each photon generates an electron, then our photodetector takes an optical input and generates an electrical current based on how bright the optical input is.

Part 2.1: Blocks on blocks on blocks

Once we move past individual building blocks, engineers often assemble these blocks into standard functions, such as: optical filters, modulators, and complete optical communication links.

Optical Filters

There are many different ways to build an optical filter out of silicon photonics building blocks. One way to do it is to use the splitter/combiner building block, and connect two of them together with the waveguide building blocks. By making one of the connections longer than the other, certain colors of light will create constructive or destructive interference patterns. Changing the size of the imbalance will change the interference pattern. Try it out yourself by dragging the long waveguide in the image. See if you can adjust the length so that only green light passes through the filter, while orange and blue light is mostly blocked:

We can create even more complicated filter shapes by cascading many of these elements together in a row. Try it out on this next filter featuring three different filters placed in a row with one another:

Modulators

An optical modulator is a device that "modulates" some property of light. Often, the property being modulated is how bright light is in order to transmit information. We can encode information onto light by turning the light on and off in specific patterns and with regular timing. For example, "off-on-on-off-off-off-off-on" could be the letter "a" and "off-on-on-off-off-off-on-off" could be the letter "b."

One common way to create an optical modulator is to insert the phase shifter from before between a splitter and combiner. This way, by changing the voltage on the phase shifter, we can change the brightness of the light coming out the other end:

And beyond

With just these few building blocks, a nearly infinite number of optical functions are possible. With just the waveguide, splitter, phase shifter, and photodetector you can construct anything from analog optical neural networks, coherent optical links, LIDAR phased array scanners, optical quantum computers, and many more things not yet invented.

If that sounds super exciting, it's because it is!

Part 2.3: Beyond the hype

So silicon photonics is pretty great, right? Well, as of early 2022, there is a good reason that all of the products based on this technology that have reached commercial success are all built for optical communication inside telecommunication or data center networks. In general, the types of chips built for most optical communications applications are relatively simple in what they do. There are usually up to four devices on a chip that can modulate the intensity of light passing through them, a few devices to split or combine light, up to four photodetectors, a method to get light from the chip into a fiber optic cable, and some sub-assembly for a light source. Even with generous methods for determining what "counts" as a device, the number of optical devices integrated onto a single chip puts most commercial silicon photonics chips somewhere in the 1960s compared to the number of transistors on computer chips. By the 1970s, several thousand devices were on the chips being produced by Intel, IBM, and others. It isn't yet clear if any silicon photonics products will emerge in the next decade with thousands of elements on a chip.

There's a tremendous amount of engineering effort that goes into designing those silicon photonics chips for optical communication. The two fundamental challenges with photonics, generally, is that it is very hard to do anything with a small amount of light and every component that light passes through loses some of it. With electronic computer chips, you can use a tiny amount of electronic charge to flip a switch--there really isn't an equivalent thing in the optical world (at least, nothing as simple). While there are demonstrations showing data transmission with a single-digit number of photons per bit of information, it takes an enormous series of electronic amplifiers to do anything meaningful with those singular photons. In terms of losing light, if you have 15 things that are all 95% transparent, you've lost more than half your light coming out the other side of those 15 things. (95% * 95% * 95% ... 15 times = 46%)

In the silicon photonics world, 95% transparent is really good for most things. But now, say you have one element to bring your light from an optical fiber onto your chip, two elements to split your light four ways, three elements to modulate your light, one element to tap off a bit of your light to monitor how much of it there is, and another 4 elements to combine your light back together. This imaginary chip exists mostly for the sake of argument, but at the end of those 11 things you now have only 56% of your light left! Losing 56% of your light would still be one of the world's best chips for optical communication because achieving 95% transparency for each of those devices is a feat of engineering.

The trick for the silicon photonics industry will be designing better and better quality devices to take that 95% up to 99%. With a set of devices that is 99% transparent, now you can use 70 different elements in a row instead of 15 and still have half your light leftover. I think this kind of performance is possible and will only be a matter of time before we see remarkably complicated systems. Until then, everything we build just has to be content with throwing away most of your light to do anything with it.

Even so, as I mentioned in part 2.1, there is a lot you can do with just a few components. I don't think the silicon photonics field has exhausted all the exciting options and opportunities, even with the present state of the art.