(Quick note, I link to a lot of academic research in this post. Most of it is behind a paywall. I was able to access pretty much everything relatively easily with or without the help of a certain hub of science. I'm sure you can, too)

Fireflies or, taxonomically, beetles in the Lampyridae family, are absolutely bonkers. Outside of this blog, I've been trying to write various pieces of fiction, and one of those stories involved fireflies. I downloaded a few pieces of scientific literature to get familiarized on the subject and I was just blown away by how insane these creatures are when viewed through a sort of anthropomorphic lens. I understand insect intelligence is wholly different from human intelligence (China Miéville's Perdido Street Station has a fun treatment of this. I think this book also falls into the bonkers category, in a good way). But still, these are rad little creatures.

In the spirit of this blog revolving around optical communication, I thought I would dive in deeper into fireflies and see if I couldn't dig up academic research on the optical communication side of fireflies. What analogues could be drawn between conventional optical communication and non-human biological optical communication? How many bits per second are they blinking at? But first, a few bonkers facts.

An article published in 1920 by Hess in The Biological Bulletin has several detailed accounts on the behavior of fireflies. This includes the gruesome take-down of an earthworm by a group of firefly larvae. The larvae feel around with their antennae and other sensory appendages until they happen upon the earthworm. The larvae bites the earthworm and, with this first bite, the earthworm reacts by moving around quickly. The firefly keeps biting the earthworm and the worm moves less and less with each bite, apparently numbed. Meanwhile, another larvae approaches the worm and bites it in a different spot, causing it to again move about quickly. By the seventh bite from the second larvae, the earthworm again stops moving. A third larvae finds the worm and bites into it in yet another spot. The worm reacts, but its reaction is significantly subdued, as if paralyzed. Hess saw the same process repeat with a snail. At first, the snail reacts to the bite from the firefly larvae, but within minutes it stops moving, evidently paralyzed.

After the larvae inject their prey with the paralyzing agent, the eating begins. I assume that the prey is devoured alive. Hess goes on to write, "while feeding on its prey, the larva keeps its jaws actively moving back and forth, apparently ejecting digestive juices from its mid-intestine by way of the mandibular canal, and with the two inner teeth on the mandibles it tears the worm to pieces and draws small portions into its mouth." In an act usually reserved for science fiction horror, firefly larvae paralyze their prey and then eat it alive. Slowly.

Hess didn't describe whether the larvae were luminescent during feeding, but fireflies have larvae that have bioluminescent capabilities that are fully functional at birth. I like to imagine the larvae gleefully glowing during their murderous feeding frenzy. For more detailed drawings of firefly larvae and their biology, Archangelsky and Branham describe some of the nitty gritty physical properties of the larvae.

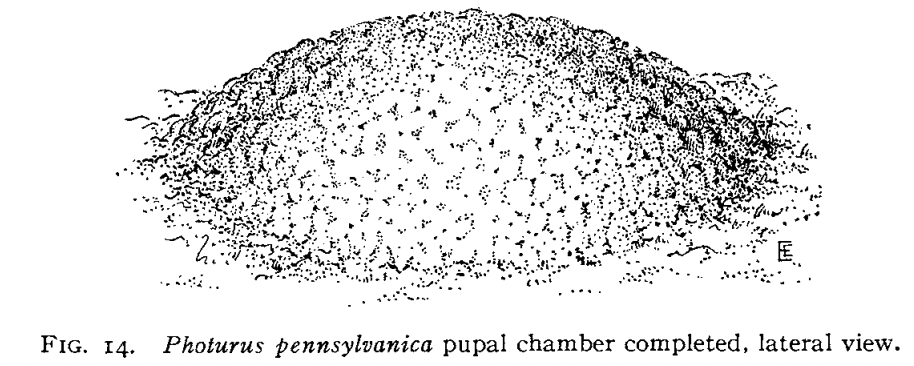

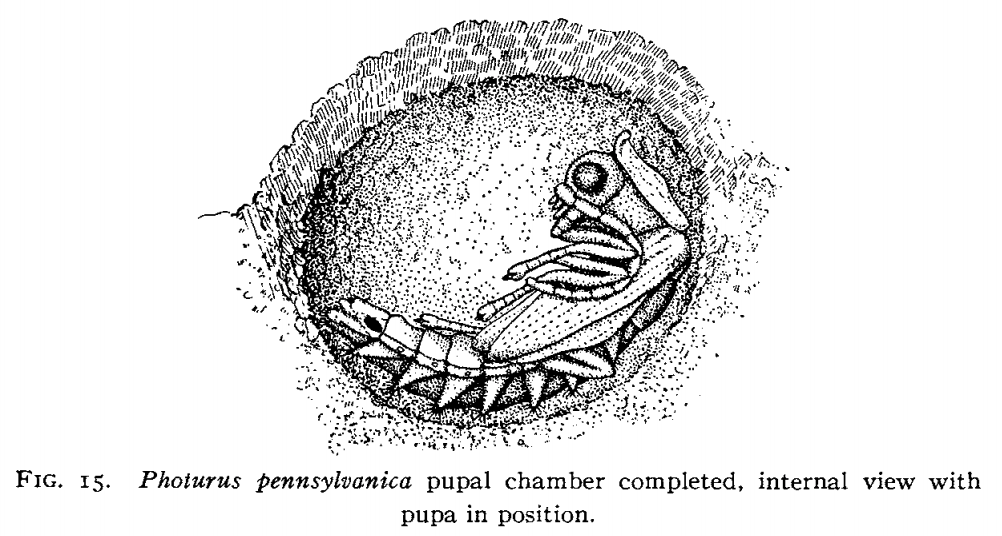

Once the feeding is done, (and more being glossed over here), it's time to pupate into their adult form. Each particular species of firefly larvae have their own structure they use to pupate. Some some hide in moist earth underneath stones to excavate their cell. Others dig a small hole in the ground, chew up pieces of earth, and regurgitate a lattice work dome chamber with walls up to half an inch thick.

After pupation, many (most?) species of fireflies do not feed as adults. Instead they engage in nightly courtship activities. General consensus, echoed in recent literature, is that bioluminescence originally emerged as an "aposematic display from nocturnal predation, and that the mating function in bioluminscence evolved separately." Proving why a certain trait evolved is a tricky problem.

In 1997, Underwood, Tallamy, and Pesek showed that firefly larvae were distasteful to mice and that the mice could be trained to associate light cues with the unsavory food. In their discussion of their results, they relate the challenges of proving aposematic roots of bioluminescence in firefly larvae to other creatures, writing "Several studies have found a correlation between bioluminescence and unpalatability, but experimental evidence supporting the aposematic display hypothesis exists only for the brittle-star, Ophiopsila riisei."

Amusingly, among their cited sources is what I can only imagine a bitter scientific feud in the style of Tesla vs. Edison or Newton vs. Leibniz. In this case the feud is between Matthew S. Grober and Tim Guilford, fighting about aposematism in marine gastropods (The aforementioned brittle-star, Ophiopsila riisei). In "Bioluminescent Aposematism: a reply to Guilford & Cuthill," Grober argues against Guilford and Cuthill's "misleading discussion of the evolution of aposematic signals." There's definitely a certain gossip-column tabloid schadenfreude pleasure reading these rebukes and rebuttals.

By whichever evolutionary pathway bioluminescence evolved in fireflies towards communication, the end result is striking. Buck and Case describe a few of the well-documented patterns (citations in the excerpt are found in the original article):

The large common American firefly Photinus pyralis is the best-known practitioner of dialog courting. The flying male emits single flashes in an ∼6-s rhythm that typically continues for many minutes whether answered or not. The perched female does not flash spontaneously but, if within a meter or two of a male, answers each of his flashes (or an artificial flash) with a single flash after an ∼2-s delay. The male does not then flash but at once (0.4 s) orients toward her. The female’s 2-s delay is the necessary and sufficient condition for the male to be attracted to her (or to an artificial light flashed after a 2-s delay) (McDermott, 1917; Buck, 1937b; Lloyd, 1966a; Case, 1984; Carlson and Copeland, 1985).

In another photinid, P. greeni, the male’s signal is not a single flash but a pair, about 1.3 s apart (27◦), repeated every 5–6 s. The female’s response flash is delivered about 0.9 s after the second flash of the male’s pair and the male does not normally respond to answers to his first flash, nor does the female respond to a single stimulus. In P. greeni, as in P. pyralis, the female is identified to a conspecific male by her fixed response latency, but in addition, she can recognize the male by timing his pair of advertising flashes (Lloyd, 1969; Buck and Buck, 1972; Buck and Case, 1986). The greeni female, like the pyralis, remains responsive through many minutes without stimulation.

One more aside: As I searched for firefly literature, I saw papers spanning seven decades all attributed to "J. Buck." I figured maybe there were multiple Bucks in the firefly research game, or perhaps it was a family tradition. It turns out the late researcher Dr. John B. Buck, did his PhD work in the 1930s on firefly research and dedicated his life studying these creatures. Among many notable contributions to science is his work in 1988 describing the synchronous flashing behavior of fireflies. Nearly every scientific field that deals with coupled systems likes to cite this paper, including papers in my own area of expertise.

On the flashing dialog of fireflies, James Lloyd writes in Scientific American in 1981 that he has observed 130 different firefly species with 80 different identifiable flash patterns. If one out of the 80 flash patterns is truly uniquely identifiable, this at least puts a floor on the number of bits communicated to Ln(80) = 6 bits. Lloyd does make sure to point out that the flashing sequence changes with temperature and other ambient conditions and that flight path and other behavior in combination with the flashing are necessary for us to uniquely identify species. I'll lump all of this behavior into the optical communication space-division-multiplexing analogue bucket so that I can consider the entire behavioral dialog sequence as optical communication.

Lloyd goes on to write how the female firefly response, in combination with the male flash pattern, is what totally differentiates species to ensure reproductive isolation. The bulk of the article focuses on the complexities of male-female flash/response behaviors in the context of male competition and female Photuris fireflies, which mimic the flash response of other species to lure males in order to eat them. Fireflies communicate in an intricate sequence of flashes, responses, competitive interjections, predator deceptions, and prey counter-deceptions that constantly change depending on the environment and in the presence of different firefly species. In some courtship patterns, rival males send competing flashes timed between their competitor's own flash.

From Lloyd's Scientific American article and other literature, it's clear more is being communicated than just a 1/80 species delineation. Carlson and Copeland outline prior research, notably for this discussion, that there are different flash patterns and responses for different stages of courtship. There is a "warmup time" before males and females are ready to send and receive flashes. A 2008 review of firefly flash evolution continues the discussion on information content in courtship. Lewis and Cratsley propose that the observed non-correlation between flash properties and mate-quality could be explained if "courtship signaling systems of different lampyrid species may vary in their location along an evolutionary continuum from reliable to uninformative to manipulative courtship signals." How many bits of information is required to manipulate another firefly?

Defining information transfer is tricky. If it is purely for guaranteeing reproductive isolation, is an entire genome encoded in the dialog? Sometimes the difference in flash behavior is correlated with just 1 basepair change in mitochondrial DNA, such as between fireflies in the Goto islands and on Kyushu, Japan, where each have a distinctive flash. With 2,200 recognized species of firefly total, and a DNA sequence thousands of base-pairs long, is this >11 bits of information transmitted in less than 10 seconds? >>11 bits of information? With the complexities of the firefly dialog behaviors, it seems reasonable that more information than just species type is communicated. There are certainly more complicated examples of insect communication, such as the Nobel prize-winning observation of honeybees' "waggle dance." Of course, surrounding all insect communication is the danger of over-applying folk psychology to instinctual behavior. We know the flashing behavior changes in the presence of certain predators, so is that another bit or two of information?

I certainly don't know. For the sake of concluding the blog post, let's put it at somewhere between 5 and 20 bits per few second period, for a data rate of ~2 to 10 bits per second.

How does this compare with what humans have come up with? In addition to long-distance sight-based communication such as smoke signals, long-distance optical communication techniques, semaphores, have been in use for a very long time. Communication via lighting beacons in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) was described by Perseus. Probably before, and definitely since then, other systems of lighting beacons or waving flags have been developed.

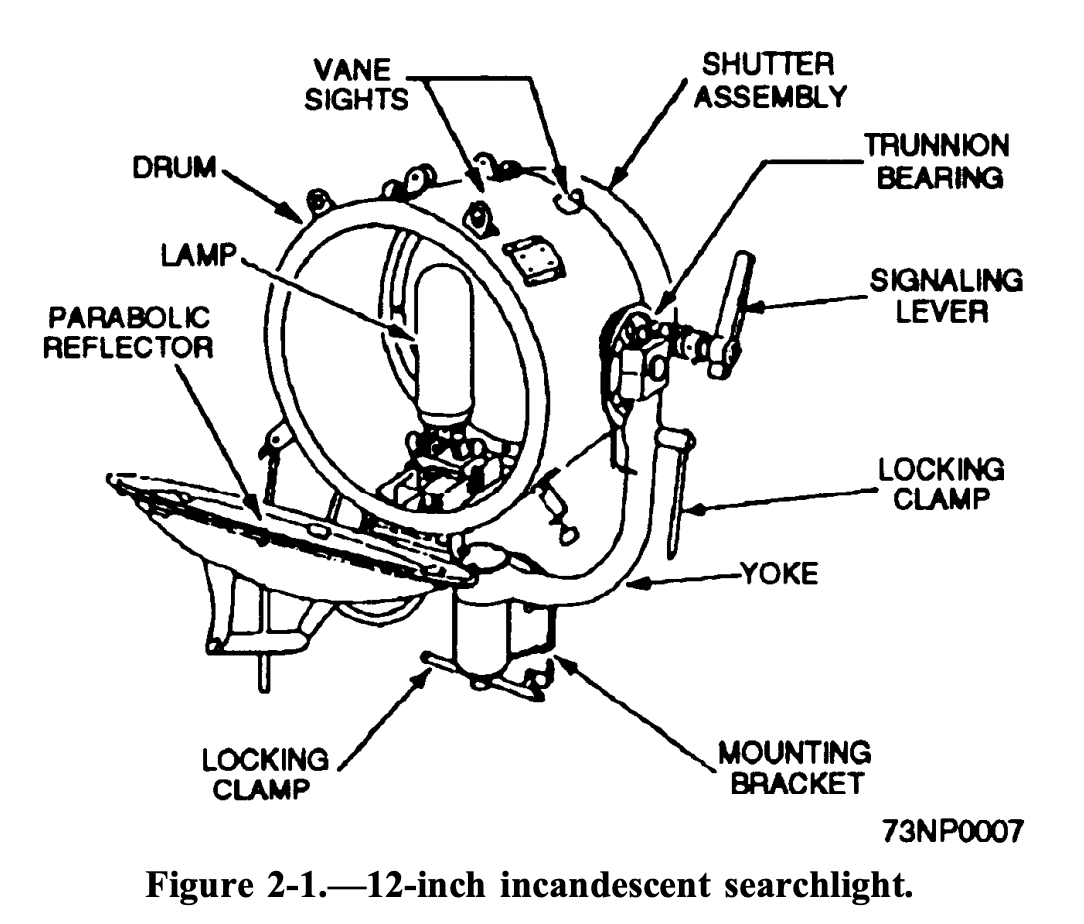

U.S. Naval searchlights have shutters that can open and close to allow up to 15 words per minute (PDF warning), with the NATO standard sending speed of 8 words per minute. I'm not clear exactly how words per minute might translate to bits per second. If an average word is 6 characters and each character is at least 1 byte, then 8 words per minute is roughly 6.4 bits per second. I know there is likely significant compression of words & spelling in semaphore communication, but I will guess this is probably within a factor of 2 or 4. So naval searchlights might send somewhere between 2-24 bits/second. Not that far ahead of our luminous little friends.